In the short run, state officials are looking at one or two tiny satellites the size of a loaf of bread, called Doves, that will expand on existing efforts to detect flares of the potent greenhouse gas from oil wells, pipelines and other sources in order to get the flares quickly shut down.

But in the long run, state officials are really envisioning a “constellation of satellites” designed to find “super emitters” of methane gas in California and elsewhere.

In short, at this point the project is being done by one private company, with oversight and in coordination with one state agency, and there's no money set aside for it in the state budget. But that company has a serious track record, and the potential for collaboration and partnerships down the road could be huge.

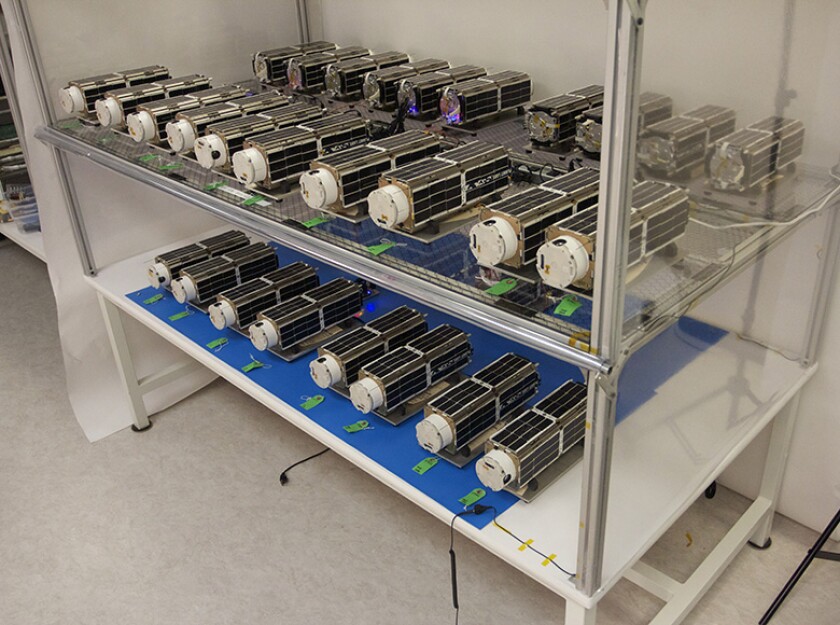

The California satellites would be built by Planet, formerly known as Planet Labs, a satellite imagery purveyor launched — where else? — in a Cupertino garage in 2010. Last month the company, founded by several former NASA scientists, opened a new 27,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in San Francisco capable of producing 40 of its small satellites a week. In the past four years, the company has launched 298 satellites, 150 of which are still in orbit collecting over 300 million square kilometers of imagery daily for clients ranging from farmers to insurance companies to state and local governments.

State officials say the sole agency overseeing the program so far is the California Air Resources Board (CARB).

Stanley Young, communications director for CARB, said the satellites will build on a 10-year-old state program designed to identify methane hot spots that uses ground-based monitoring and an airplane to detect significant emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas.

Young said the statement of intent calls for Planet to build and launch the satellites and to provide data to the state at no cost. The state will be responsible for “porting” infrared detection technology into something that can be used in a satellite.

“We are working with Planet to identify the right instrument, which will be some type of hyperspectral imager. There are many different options out there even beyond what was used during the California Methane Survey,” he said.

“The ribbon of Earth a satellite would scan is about 50 miles wide,” Young said. “Eventually we want to cover the entire planet with a constellation of satellites, maybe a dozen or so crisscrossing the planet.

“They could cover relevant areas in a day or so and help us pinpoint blowouts at storage facilities, oil and gas wells, or even a pipeline in just a few hours short of real time. We can then notify the owner and require them to shut it down.”

With only one or two satellites, Young acknowledged that the data the state would receive would just be one small step toward the giant leap envisioned. He declined to speculate on when the program could be operational because it’s in such an early state of development. He acknowledged it would take at least two to three years at a minimum.

“At this stage, there is no state funding,” Young emphasized. State officials believe that philanthropic and private-sector funding will provide the bulk of the money for the project, pointing to $3 million already pledged by nonprofit foundations. He did acknowledge that CARB may have to ask the state for additional computing and staff resources should a satellite constellation become a reality.

“The time between revisits to any particular area will be weeks to months,” he said. “After the initial satellite has proven the concept, the effort could be expanded to a constellation allowing for near-daily revisits of major methane-emitting infrastructure around the globe.”

Agriculture contributes roughly 60 percent of the methane released in California each year — much of it from cows in dairies — with landfills and industry contributing 20 percent each. The southern San Joaquin Valley is a large methane producer due to the concentration of dairies and oil fields there, with other major sources in the Bay Area and Southern California because of refineries and power plants. CARB says storage tanks and wellheads are responsible for the largest fraction of methane plumes.

Other uses for the data gleaned by the Doves for the state could include evaluating wildfire risk, ecosystem health, soil health and composition — allowing for “precision farming” — mineral exploration and geological hazards.

Combating methane emissions is an important part of California’s climate change program. Legislation enacted in 2015 required the state to investigate methane emission “hot spots” because, as Young noted, state officials know where dairies and landfills are.

Planet officials did not respond to requests for comment, but Young said the company is participating because it believes methane needs to be cleaned up and other foundations and individuals concerned about climate change will also contribute.

The company’s business model is to build relatively inexpensive satellites with just a one- to three-year life expectancy and place them into low-Earth orbit, about 150 miles above the surface. Because they’re designed for short missions, they don’t need the radiation protection that satellites that will be in use for a decade or more would, and because they’re small and in low-Earth orbit, launch costs are also significantly less, Young said.

While large satellites built and launched by the federal government may cost a billion dollars or more, Planet’s Doves can be built for a fraction of that, although as a privately held company they have declined to publicly discuss costs.

John Markham, a tech stock analyst, wrote in a Forbes piece earlier this year that the cost is just “a few thousand dollars.”

Because the Planet satellites are so small, the company is able to launch dozens at a time. In 2017, the Los Angeles Times reported, Planet launched 88 of its Doves aboard the Indian Space Research Organisation’s PSLV rocket, and then five months later sent up 48 Doves on a Russian Soyuz rocket.

Brown made his announcement at the conclusion of the Global Climate Action Summit he convened in San Francisco to bolster support of efforts to combat climate change in light of the Trump administration’s skepticism of the impact of human-caused greenhouse gases on the world’s climate. He had first advanced the idea at the end of 2016 at a conference of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, saying: “If Trump turns off the (NASA) satellites, California will launch its own damn satellites.”

The Governor’s Office declined to comment on the need for satellites that will revisit specific locations in California only every few weeks or months, pointing to the press release issued when the announcement was made.

John Frith is a Folsom-based writer and editor with a background in state, local and federal legislative affairs as well as journalism and public relations.